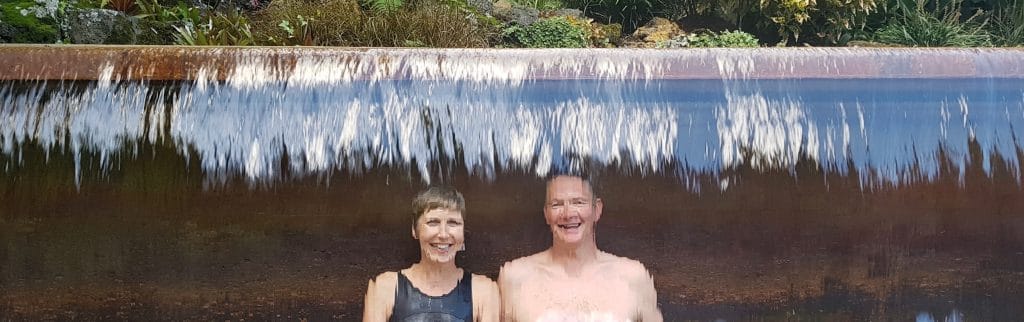

This week I’ve been working with Kerry and Roger. They hope to enjoy swimming breaststroke in long, deep pools on holiday in Cyprus next month. They’d like to swim without anxiety or strain and to be able to keep going.

There’s an optimum way of swimming breaststroke, centred around getting the head out for unhurried inhalation. Ideally, breaststroke is a series of glides, or dives. The tricky thing is you need to keep your arms in front of your body. And every human being untrained in the art of swimming wants to pull their arms all the way back, to create propulsion. Gliding in breaststroke is counter-intuitive.

According to the Alexander principle, if your neck’s free when swimming, you’re getting the most important thing right. But if you strain your neck either by striving to get your stroke right or by swimming without awareness of your neck, then you can go horribly wrong. The most important thing is not to strain your neck.

For most adults learning to swim, no amount of drilling or practice changes the strong, instinctive tendency to pull the arms back to move forward. The problem with dominant arms is that they hinder a relaxed, free-necked, in-breath.

So Kerry and Roger found it almost impossible to glide, with arms out in front, in breaststroke. Without propelling themselves with their arms, they couldn’t get themselves going. The more they tried to get the stroke right, attempting to execute coordination patterns which didn’t make sense to them, the less progress they made through the water and the stiffer their necks became.

Anxiety about breathing/ drowning and anxiety about getting movements right are closely linked and reinforce each other. Kerry rendered herself quite hopeless as soon as she perceived herself unable to get a new coordination pattern.

If I’d spent all week trying to get Kerry and Roger to find the elusive glide, they’d have hit a wall and got more and more frustrated. They wouldn’t have learnt to get their head out to breathe and their holiday swimming plans would have been on hold.

So we needed to find a compromise. The ‘holiday breaststroke’ on the video clip isn’t conventional breaststroke. Something deeply ingrained but ‘incorrect’ has remained dominant. But it works. It gets Kerry and Roger moving. And it’s fine, so long as it doesn’t cause them strain and anxiety when coming up for air.Both of them are relaxed about inhalation, Roger so much so that he lets the air come in through his nose. This is because they’ve learned to change the movement pattern of their arms, not throughout the stroke but just when support for the breathing position is needed. This much change is manageable for them. Instead of trying to come up for air every stroke, they’re getting themselves going with a few strokes by doing what’s natural with the arms then, when a breath is needed, keeping the arms forward and using them in a different way. For Kerry, being able to come up to breathe without stress is a hugely significant step.

Kerry and Roger know they’re not swimming like Olympians but they feel good. They’re enjoying this way of swimming and it will keep them going as far as they like. Their necks are free and their breathing isn’t rushed or forced. They feel like competent, recreational swimmers. And there’s a freedom in that.