“I need front crawl for aerobic fitness,” said Joe today. He doesn’t believe his beautifully coordinated breaststroke gives him enough of a workout, but a physical disability prevents him from lifting and fully extending one of his arms. Partly because of this, his front crawl is a rushed, gaspy affair, causing twisting of his back and tension in his neck. While helping him to make it more gentle and efficient, I had to question his desire to do it.

For most of my adult life I’ve entered the pool in lane swimming sessions with the same kind of thinking as Joe. I’ll swim so many lengths of front crawl in so much time, hoping to attend to technique of course, but with the agenda of improving my cardiovascular fitness. With such an agenda, there’s usually a cost, depending on our level of coordination….

Front crawl promotes asymmetry in the body. We may not be conscious of how asymmetrical we are. We may feel our stroke to be beautifully symmetrical. But as human beings our basic one-sidedness is going to reveal itself in front crawl, even if we don’t feel it.

Front crawl requires constant rotation of the body with the head still. Deep down, subconsciously, most of us want to turn our head at the neck when our body turns. The conflict between the decision to let your head lead and the inner desire to turn it when your body rotates causes neck tension.

Front crawl breathing involves turning to get a breath. Even the tiniest bit of a struggle to coordinate our breath with the stroke results in neck tension, tightening of the jaw and a gaspy breath. And for people with sensitive vestibular systems, or poor balance, the required frequency of turning is just too much for the nervous system.

The kind of breathing we do when swimming front crawl isn’t usually the kind of breathing that happens naturally, when we’re leaving ourselves alone. It’s almost impossible to get air in without overdoing it.

And if we’re gasping and sucking in air, inhaling even a little bit more than we need, and what we’re inhaling is the air sitting on the surface of heavily chlorinated water, perhaps we should wonder whether our efforts are worthwhile.

Here’s what I remind myself…

- Don’t do too much swimming up and down in chlorinated water.

- In the pool, slow everything right down and work for a few moments of connection, of integration.

- Don’t push yourself if it means tightening your neck or gasping.

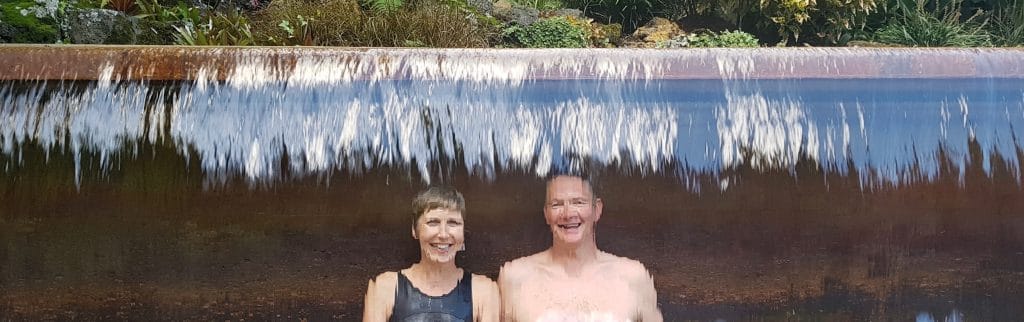

- Swim outdoors and enjoy support from your natural environment as often as possible.

- Aim to come out energised, with nothing depleted.

If this post resonates, have a look at the Ameo Powerbreather, which you can order from our shop. Don’t forget your newsletter subscriber discount code.